Anodized mirror aluminum coil

At first glance, an anodized mirror aluminum coil looks like a simple object: a ribbon of metal that happens to be very shiny. But behind that reflective surface lies a quiet convergence of metallurgical chemistry, surface physics, and tightly controlled industrial practice. To understand this material properly, it helps to think of it less as “decorative metal” and more as a calibrated optical component delivered in coil form.

Instead of starting with its applications, consider how unforgiving a mirror actually is. Any imperfection in the substrate, inconsistency in alloy chemistry, or minor variation in oxide growth reveals itself immediately as haze, distortion, or color shift. That is precisely why the story of anodized mirror aluminum coil really begins not at the finishing line, but at the casting furnace and rolling mill.

The alloy beneath the reflection

Mirror-quality anodized surfaces demand a substrate that is both optically friendly and anodizing-friendly. This is why producers rarely choose high-strength aerospace alloys for this purpose. Those alloys are rich in copper, zinc, or magnesium, which can cause non-uniform oxide growth, pitting, or discoloration during anodizing.

Instead, mirror anodized coil typically comes from high-purity or low-alloyed series such as 1xxx, 3xxx, or selected 5xxx grades. A typical choice for high-reflectivity, good formability, and clean anodizing behavior might look like this:

- 1050/1085 for very high purity and maximum specular reflectance

- 3003/3005 when moderate strength and better formability are needed

- 5005 when structural integrity and façade-grade weathering are required

A representative chemical composition table for a mirror-anodizing-friendly alloy (such as 5005) would be:

| Element | Typical Range (wt%) |

|---|---|

| Si | ≤ 0.30 |

| Fe | ≤ 0.70 |

| Cu | ≤ 0.20 |

| Mn | ≤ 0.20 |

| Mg | 0.50–1.10 |

| Cr | ≤ 0.10 |

| Zn | ≤ 0.25 |

| Ti | ≤ 0.10 |

| Al | Balance |

The low levels of copper and zinc help avoid troublesome intermetallics that interfere with anodic film growth. Magnesium is present for strength but controlled so that the anodized surface remains uniform and stable in color.

Purity is not a marketing flourish here; it is an optical necessity. Microscopic inclusions or segregated phases scatter incident light and destroy specular reflection. What looks like “just alloy content” in a datasheet is, from a mirror perspective, a map of potential defects.

Temper and flatness: mechanical discipline for optical performance

The temper designation of an anodized mirror aluminum coil is often treated as a mechanical footnote. In reality, it is the second half of the optical story.

Common tempers such as H14, H16, or H18 in cold-rolled material do more than define yield strength. They determine how the coil behaves under tension leveling, slitting, and forming – and thus how well the final surface resists “orange peel,” waviness, or stress-induced distortion that ruins the mirror image.

A typical property range for a 0.5 mm thick 5005-H14 anodized mirror coil might be:

- Tensile strength: 140–185 MPa

- Yield strength: 110–150 MPa

- Elongation (A50): 5–10%

This balance enables controlled forming without deep surface cracking or grain-boundary stepping that would show up in reflection. Flatness is equally critical. A piece of mirror aluminum that looks visually flat on the table can still produce funhouse reflections if the rolling and tension leveling are not carefully tuned.

The result is a material that is mechanically modest by structural standards, yet highly engineered from the standpoint of surface stability.

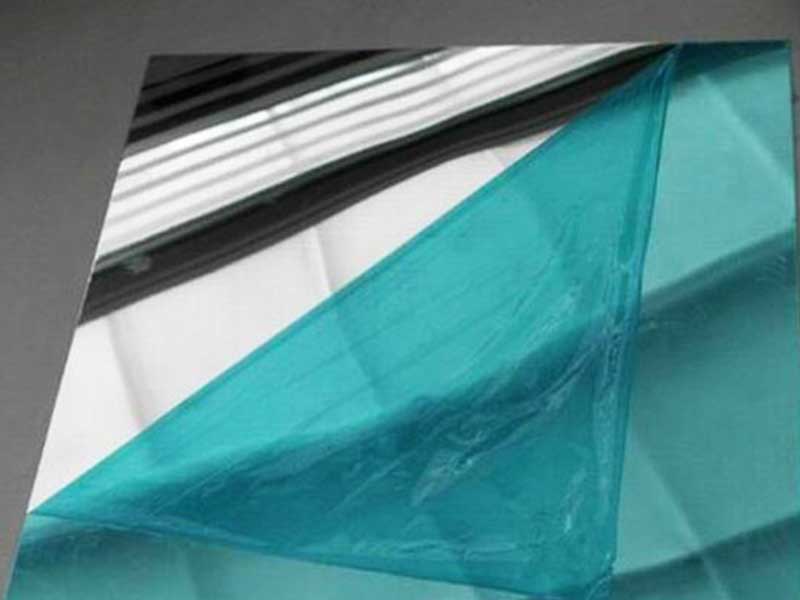

The mirror that is not just polished: pre-anodizing surface engineering

Anodized mirror aluminum coil is not “just anodized polished aluminum.” The route to a true mirror grade involves deliberate control at several stages:

- Precision cold rolling to reach the target gauge with minimal surface chatter

- Specialized bright rolling or mechanical polishing to achieve a pre-anodizing gloss

- Degreasing and alkaline or acidic cleaning to remove rolling residues

- Fine etching or chemical brightening, depending on the desired reflectance and surface texture

Chemical brightening, often using nitric- and phosphoric-based solutions, subtly dissolves micro-roughness peaks, allowing for a more specular base. Every micron of roughness at this stage multiplies its effect later. For high-specular coils, pre-anodizing reflectance can reach above 80% before the oxide film is even formed.

Surface roughness, often in the Ra 0.02–0.06 µm range for high-end mirror finishes, is not a luxury; it is the boundary between “almost mirror” and true specular reflection.

Anodizing as a controlled optical coating

Anodizing is frequently described as a simple oxidation process. For mirror coil, that phrase fails to capture how engineered the oxide really is. During sulfuric acid anodizing, the aluminum substrate is converted into a porous layer of aluminum oxide, with growth typically in the range of 3–25 µm depending on application.

For mirror applications, the anodic layer serves several simultaneous functions:

- It locks in the polished metal surface beneath, preserving the original optical geometry.

- It provides a hard, scratch-resistant, corrosion-resistant skin.

- It enables subtle tuning of color and reflectance, especially when combined with dyeing or electrolytic coloring.

Typical anodic film parameters for mirror coil might be:

- Coating thickness: 5–10 µm for interior decorative use

- Coating thickness: 15–20 µm for exterior façade and architectural elements

- Hardness: around 300–500 HV depending on process conditions

- Adhesion: integral to substrate (no interface in the conventional sense, as the metal transforms into oxide)

Because the oxide is transparent to visible light, its microstructure must remain uniform. Non-uniform pore distribution, burn marks, or micro-cracks act like random lenses and scatterers, degrading the specular quality. The anodizing line becomes not just a corrosion-protection station, but an optical coating facility in disguise.

Standards and repeatability: from art to specification

The transition from “nice shiny metal” to industrially useful “anodized mirror coil” happens when reflection, color, hardness, and durability are defined in standards.

Architectural and façade-grade coils are often produced to meet the spirit or specifics of standards such as:

- EN 485 and EN 515 for wrought aluminum and temper specifications

- EN 13523 or equivalent for coil-coated and surface property testing

- ISO 7599 for anodizing of aluminum and its alloys (thickness, sealing quality, and corrosion resistance)

Optical performance is generally captured in terms of total reflectance, specular reflectance, and gloss at specified angles (often 60° or 20°). For high-specular mirror coils, specular reflectance values above 80–85% are common, and gloss units can exceed 800 at 60°, depending on measurement conditions.

Color consistency is managed using CIELAB or similar color spaces, with ΔE tolerances often tightened for façade components to keep entire building surfaces visually uniform.

These standards transform a reflective coil into a predictable engineering product. A designer specifying mirror aluminum for a light fixture, solar reflector, or interior cladding is not simply asking for “shiny aluminum,” but for a precisely repeatable optical and mechanical profile.

Beyond appearance: function hiding in reflection

The most revealing way to think about anodized mirror aluminum coil is to recognize what its reflection actually does in practice.

In lighting systems, the high-specular surface redirects light with minimal scatter, raising luminaire efficiency without changing lamp power. The coil’s continuous format allows reflectors and linear components to be punched, bent, and rolled at scale without sacrificing reflectivity.

In solar and daylighting applications, carefully controlled specular and diffuse components determine how sunlight is concentrated or distributed. Anodized mirror aluminum offers a balance of reflectance, weight, and corrosion resistance that glass mirrors cannot match in many outdoor or large-scale installations.

In architecture, the mirror surface is not just decorative. It helps manage visual depth, apparent volume, and perceived brightness of spaces. The hardness and UV stability of the anodic film provide long-term exterior durability that organic coatings struggle to match, especially where a metallic, non-paint look is desired.

Even in consumer products and electronics, the anodized mirror finish adds more than aesthetic value. The oxide layer improves fingerprint resistance, enhances wear resistance, and provides a surface suitable for laser marking without flaking or delamination.

A quiet intersection of disciplines

Seen from a distance, anodized mirror aluminum coil is only a bright band of metal. Close up, it represents the intersection of alloy design, thermomechanical processing, surface preparation, electrochemistry, and optical engineering. Each coil carries the memory of its casting chemistry, rolling history, and anodizing bath conditions.

For customers and designers, the practical takeaway is clear: when specifying anodized mirror aluminum coil, you are not just choosing a finish. You are selecting an engineered optical surface whose performance depends on alloy family, temper, surface roughness, anodic film thickness, and adherence to relevant standards. The more precisely those parameters are defined, the more reliably that bright, mirrored strip of aluminum will perform far beyond mere appearance.

https://www.aluminumplate.net/a/anodized-mirror-aluminum-coil.html